Didier Chamizo has a more intriguing story than most, an activist who was involved in the May 1968 protests in Paris, he demonstrated against the Vietnam War and advocated for women’s liberation. Chamizo has lived a rebellious life, serving several prison sentences and taking up painting whilst incarcerated, channelling his experiences and emotions into his art and going on to have sell-out art exhibitions and advocate for prisoners to have access to art materials, which led to a pardon by President Mitterrand.

Collectors of Chamizo’s work include Alain-Dominique Perrin, President of the Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain, Emmanuel Tattinger, Marisa Berenson, and French singer-songwriter Renaud. An Arte TV documentary about his life is currently in production, and he has enjoyed an international career, exhibiting in many countries with well-known artists such as Niki de Saint Phalle and Jeff Koons, although the exhibition at D’Stassi is his first UK solo show. Chamizo’s signature style is known as ‘lettric abstraction-figuration’ or abstraction-figuration-lettrique, and ischaracterised by raw expression stemming from a colourful life of activism, incarceration, reform and creation.

Fresh from the opening of Rebel Soul, his first UK solo exhibition at D’Stassi Art, Didier Chamizo spoke to Lee Sharrock for FAD Magazine.

How did you choose which paintings to exhibit at D’stassi Art?

To be perfectly frank, I explained my paintings to our friends at D’Stassi gallery. I explained the details, the whys and wherefores: my human rights period, freedom period, revolution period. Then, afterwards, I went back to the style with the letters to work on other things, letters with capitals, then curved letters. And they made their choice. It was a very intelligent choice, and I trusted them completely.

Can you explain the inspiration behind the different types of canvas they have at D’stassi Art? How are you inspired? What’s the process like?

In terms of inspiration, there are several things going on. I have a personal pictorial language, and I’m a witness to the eras I have lived through, so public figures, singers, politicians, film actors, or even sometimes war, or human rights issues have all informed my work. When I’m thinking, I’m fed with lots of images, and then what’s left is the synthesis that allows me to make a painting. But I have a vision of the finished painting, and then I realize it.

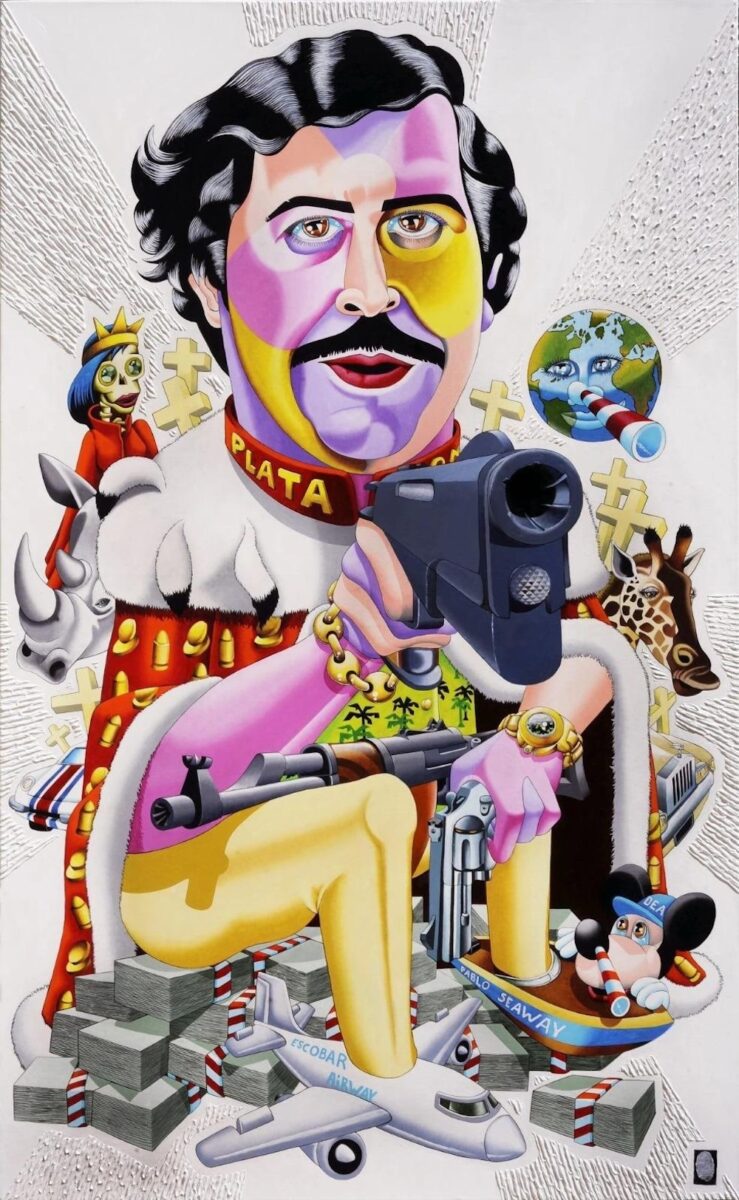

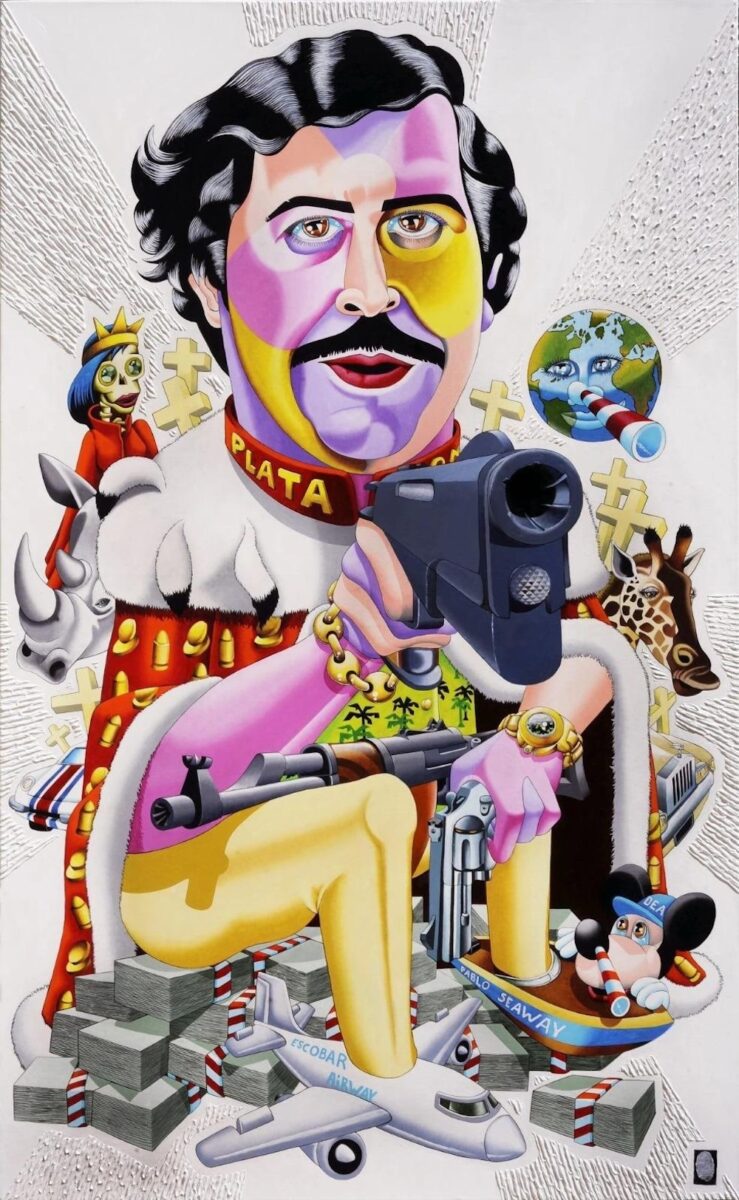

The Rebel Soul exhibition includes portraits of Sir Elton John and Pablo Escobar. Why did you choose them as subjects for your paintings?

I painted Elton John, firstly because I like his music. Plus, I’ve always found him to have a wacky personality. It was as if he’d been the Beatles all rolled into one. He’s a great popular artist. And it just so happened that I ran into Elton John a few years ago, at an event organized by Alain Dominique Perrin with his wife, Mathé Perrin. So he came to Paris, and dedicated his concert to Alain Dominique Perrin, who is a very dear friend of mine. So I said, I’m going to honour him, and if he’s ever interested, I’m ready to offer a painting for his Elton John AIDS Foundation.

Pablo Escobar is astonishing. He’s a character who was born in another world, where cocaine trafficking didn’t exist. He seized opportunities. He was something of a ‘revolutionary’ before becoming a criminal. But he’s an extraordinary figure of our time, who everyone knows. And why is a character like that interesting? Just because he’s an extraordinary character and a kind of romantic character in a strange way.

A highlight of Rebel Soul is your painting Bleu, Blanc, Rouge, what was the inspiration behind that?

The painting Bleu, Blanc, Rouge was inspired by the French Revolution. You have to know that I was Laureate of the mission for the Bicentenary of the French Revolution. Well, I was incarcerated at the time, but thanks to my work, I was part of this event. So I painted a lot of pictures that were like that, made from photographs, that conveyed messages. And here, in the painting Bleu, Blanc, Rouge, we see the Revolution, equality and fraternity. So I did a few paintings like that. Just before that, in 1986, we celebrated France’s gift of the Statue of Liberty to America, so I also painted some Liberty paintings. I believe that everyone has the right to life, liberty and security.

And what’s the story behind the Harley Davidson featured in the exhibition that you’ve hand-painted?

So, on the Harley Davidson, initially, my friends at the Dirty Cats motorcycle workshop wanted to customize a Harley that told a bit of my story…for example, the engine is a 1991 Harley Evo model (the year I was released from prison), and the styling is inspired by the ’60s and ’70s, which were the years of my youth before my incarcerations. So they gave me Punk-Rock as a theme, because it’s the British music I love, and the Rebel Soul exhibition is in England of course! So from then on, the Punk period included singers like the Sex Pistols and the Clash. It was also a period of Rock’n’Roll that was very destructive. So when we talk about Rock’n’Roll, and especially Punks, we can’t avoid beer, alcohol and various drugs. I depicted Amy Winehouse on the side of the bike. Amy was a great singer whose life was unfortunately cut short due to various excesses.

Your paintings are inspired by Lettrism, an alternative to graffiti and tag art, and your style has been described as abstraction-figuration-lettrique. Can you tell us a bit about that?

First of all, I was interested in painting in general, with the great masters, but I’ll come back to that a little later. Lettrism, in fact, in theoretical painting, pretty much stops at Saït-Ombli. And by doing my abstractions on the ground and by doing these abstractions of human rights on the walls, I was practically the first, at a time when street art was called urban art, to do abstract tags that were paintings. But what happened was, while I was making these abstract tags, I saw bits of letters that looked like ribs, or a nose, or an eye socket, and I started working on them to make abstract-literature, figurative-literature. After that, a few people followed me, inspired by my reintroduction of volumes in painting. In other words, we’d already had trompe-l’œil, which was photographic perfection. But with cinema, video and video games, we find ourselves with a different, more saturated chromatic range. And also, a reintroduction on my part of neo-perspectives, because painting can’t only be inspired by nature. But all of a sudden, painting could take an interest in modern images and study sections and sections of imagery. We’ve got neo-pop art, new stuff, but in fact, there are tremendous sources of inspiration in terms of color and perspective in games, the colours of the chromatic scale, television too, in particular.

So, if we go back chronologically, when you started painting, who were you inspired by, for example?

Well, first of all, I have to say one thing, I really love painting and I’ve been interested in everything from African sculptures – I first did a sculpture mission for AIDS with the Macondés – to the great masters of painting, from Cézanne to Caravaggio, via Leonardo da Vinci, or even the creative freedom of Picasso. I also love Dali. In terms of inspiration, I can’t say that I try to draw inspiration from others, because I do everything I can to make my work look like Chamizo and nobody else.

I think there’s a hyper-realistic, psychedelic aesthetic in your paintings that reminds me of Ralph Steadman’s illustrations for Hunter Thompson’s book Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. What do you think?

I like Ralph Steadman’s work a lot, with its social criticism and humour, and it’s true that I do it a little bit with love too, by choosing extraordinary personalities, with a certain criticism or sometimes a lot of love, because we’re of the same race of primates.

You’ve had a very eventful life, made up of activism and rebellion, hence the title of the exhibition Rebel Soul. How have you channelled your emotions and life experiences into your art?

I think art is something very important for me, because it allows me to express myself, and indeed it allows me to endure the cries of the world, the misfortunes, the wars, but also extraordinary things.

When you were in prison, how did painting help you?

When I was in prison, I was part of the phenomena that created the Prison Action Committee, and we changed prisons in the 70s, which hadn’t moved since, I’d say, the beginning of the 20th century. As a result, in addition to painting, which allowed me to feel good, we created a newspaper- well, it already existed, but we improved it enormously, it was in all the editorial offices, it was the political conscience of French prisoners. We organized movements, hunger strikes, rebellions too, to achieve a prison that was more liveable for everyone. I’ve always painted every day, and when I was in prison, I used as a cell as a studio, which was next to the cell used by the newspaper The Lock, I had visitors, guards who came in and out. I can paint anywhere.

Do you find artistic practice cathartic and do you think it’s a good conduit for emotions and a mode of therapy that can help incarcerated people, in particular?

As far as the figuration of emotions is concerned, of course. I’ve been thinking about this and I’ve put together a dossier for the Minister of Justice on this very subject, on the subject of art and prison.You have to realize that out of every 1,000 inmates, if you put a soccer ball in there, 800 will be playing soccer. If you put in paintbrushes, 5 or 6 will be interested. So, yes, it can be a good vehicle to elevate yourself and also have a different personality from the one that landed you in prison. I think it’s very interesting. It doesn’t work miracles unfortunately, but I think art does have a therapeutic effect.

Have you had people take up drawing, painting, discovering not necessarily a vocation, but perhaps a passion? And do people call you back today to thank you, for example, for having met you in prison?

As far as thanks are concerned, I’ve had many, many letters from parents, mothers and inmates too. But the inmates were very supportive.

When you work, what is your artistic process? Can you tell us a little about your painting process?

Well, first of all, I start with an idea, I feed this idea with documentation and then I synthesise it to get what I’m going to illustrate, what I’m going to use. When I draw, I first draw in charcoal to compose the picture, but I already see the finished picture, I know where I’m going to put the arm, the hand, the head, how I’m going to compose it, so I draw directly in charcoal. After that, I clean it up with pencil, because I use a lot of very bright colours, so I clean everything up well, erase everything and redo the very fine lines so that I have perfect definition and no graphic build-up in my colours, so that it stays really neat.

After that, I clean it up with pencil, because I use a lot of very bright colours, so I clean everything up well, erase everything and redo the very fine lines so that I have perfect definition and no graphic build-up in my colours, so that it stays really neat. I also think that the accidents in painting that have nourished art, I’d say, from the Impressionists to conceptual art, all these accidents have meant that with three colours, after a while, it’s important to have a craft, to know how to draw in order to be able to create something new. It’s no longer possible to draw like a child or a psychiatric patient at breakneck speed, because once you’ve done that, the result is something that no longer evolves.

Didier Chamizo has a more intriguing story than most, an activist who was involved in the May 1968 protests in Paris, he demonstrated against the Vietnam War and advocated for women’s liberation. Chamizo has lived a rebellious life, serving several prison sentences and taking up painting whilst incarcerated, channelling his experiences and emotions into his art and going on to have sell-out art exhibitions and advocate for prisoners to have access to art materials, which led to a pardon by President Mitterrand.

Collectors of Chamizo’s work include Alain-Dominique Perrin, President of the Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain, Emmanuel Tattinger, Marisa Berenson, and French singer-songwriter Renaud. An Arte TV documentary about his life is currently in production, and he has enjoyed an international career, exhibiting in many countries with well-known artists such as Niki de Saint Phalle and Jeff Koons, although the exhibition at D’Stassi is his first UK solo show. Chamizo’s signature style is known as ‘lettric abstraction-figuration’ or abstraction-figuration-lettrique, and ischaracterised by raw expression stemming from a colourful life of activism, incarceration, reform and creation.

Fresh from the opening of Rebel Soul, his first UK solo exhibition at D’Stassi Art, Didier Chamizo spoke to Lee Sharrock for FAD Magazine.

How did you choose which paintings to exhibit at D’stassi Art?

To be perfectly frank, I explained my paintings to our friends at D’Stassi gallery. I explained the details, the whys and wherefores: my human rights period, freedom period, revolution period. Then, afterwards, I went back to the style with the letters to work on other things, letters with capitals, then curved letters. And they made their choice. It was a very intelligent choice, and I trusted them completely.

Can you explain the inspiration behind the different types of canvas they have at D’stassi Art? How are you inspired? What’s the process like?

In terms of inspiration, there are several things going on. I have a personal pictorial language, and I’m a witness to the eras I have lived through, so public figures, singers, politicians, film actors, or even sometimes war, or human rights issues have all informed my work. When I’m thinking, I’m fed with lots of images, and then what’s left is the synthesis that allows me to make a painting. But I have a vision of the finished painting, and then I realize it.

The Rebel Soul exhibition includes portraits of Sir Elton John and Pablo Escobar. Why did you choose them as subjects for your paintings?

I painted Elton John, firstly because I like his music. Plus, I’ve always found him to have a wacky personality. It was as if he’d been the Beatles all rolled into one. He’s a great popular artist. And it just so happened that I ran into Elton John a few years ago, at an event organized by Alain Dominique Perrin with his wife, Mathé Perrin. So he came to Paris, and dedicated his concert to Alain Dominique Perrin, who is a very dear friend of mine. So I said, I’m going to honour him, and if he’s ever interested, I’m ready to offer a painting for his Elton John AIDS Foundation.

Pablo Escobar is astonishing. He’s a character who was born in another world, where cocaine trafficking didn’t exist. He seized opportunities. He was something of a ‘revolutionary’ before becoming a criminal. But he’s an extraordinary figure of our time, who everyone knows. And why is a character like that interesting? Just because he’s an extraordinary character and a kind of romantic character in a strange way.

A highlight of Rebel Soul is your painting Bleu, Blanc, Rouge, what was the inspiration behind that?

The painting Bleu, Blanc, Rouge was inspired by the French Revolution. You have to know that I was Laureate of the mission for the Bicentenary of the French Revolution. Well, I was incarcerated at the time, but thanks to my work, I was part of this event. So I painted a lot of pictures that were like that, made from photographs, that conveyed messages. And here, in the painting Bleu, Blanc, Rouge, we see the Revolution, equality and fraternity. So I did a few paintings like that. Just before that, in 1986, we celebrated France’s gift of the Statue of Liberty to America, so I also painted some Liberty paintings. I believe that everyone has the right to life, liberty and security.

And what’s the story behind the Harley Davidson featured in the exhibition that you’ve hand-painted?

So, on the Harley Davidson, initially, my friends at the Dirty Cats motorcycle workshop wanted to customize a Harley that told a bit of my story…for example, the engine is a 1991 Harley Evo model (the year I was released from prison), and the styling is inspired by the ’60s and ’70s, which were the years of my youth before my incarcerations. So they gave me Punk-Rock as a theme, because it’s the British music I love, and the Rebel Soul exhibition is in England of course! So from then on, the Punk period included singers like the Sex Pistols and the Clash. It was also a period of Rock’n’Roll that was very destructive. So when we talk about Rock’n’Roll, and especially Punks, we can’t avoid beer, alcohol and various drugs. I depicted Amy Winehouse on the side of the bike. Amy was a great singer whose life was unfortunately cut short due to various excesses.

Your paintings are inspired by Lettrism, an alternative to graffiti and tag art, and your style has been described as abstraction-figuration-lettrique. Can you tell us a bit about that?

First of all, I was interested in painting in general, with the great masters, but I’ll come back to that a little later. Lettrism, in fact, in theoretical painting, pretty much stops at Saït-Ombli. And by doing my abstractions on the ground and by doing these abstractions of human rights on the walls, I was practically the first, at a time when street art was called urban art, to do abstract tags that were paintings. But what happened was, while I was making these abstract tags, I saw bits of letters that looked like ribs, or a nose, or an eye socket, and I started working on them to make abstract-literature, figurative-literature. After that, a few people followed me, inspired by my reintroduction of volumes in painting. In other words, we’d already had trompe-l’œil, which was photographic perfection. But with cinema, video and video games, we find ourselves with a different, more saturated chromatic range. And also, a reintroduction on my part of neo-perspectives, because painting can’t only be inspired by nature. But all of a sudden, painting could take an interest in modern images and study sections and sections of imagery. We’ve got neo-pop art, new stuff, but in fact, there are tremendous sources of inspiration in terms of color and perspective in games, the colours of the chromatic scale, television too, in particular.

So, if we go back chronologically, when you started painting, who were you inspired by, for example?

Well, first of all, I have to say one thing, I really love painting and I’ve been interested in everything from African sculptures – I first did a sculpture mission for AIDS with the Macondés – to the great masters of painting, from Cézanne to Caravaggio, via Leonardo da Vinci, or even the creative freedom of Picasso. I also love Dali. In terms of inspiration, I can’t say that I try to draw inspiration from others, because I do everything I can to make my work look like Chamizo and nobody else.

I think there’s a hyper-realistic, psychedelic aesthetic in your paintings that reminds me of Ralph Steadman’s illustrations for Hunter Thompson’s book Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. What do you think?

I like Ralph Steadman’s work a lot, with its social criticism and humour, and it’s true that I do it a little bit with love too, by choosing extraordinary personalities, with a certain criticism or sometimes a lot of love, because we’re of the same race of primates.

You’ve had a very eventful life, made up of activism and rebellion, hence the title of the exhibition Rebel Soul. How have you channelled your emotions and life experiences into your art?

I think art is something very important for me, because it allows me to express myself, and indeed it allows me to endure the cries of the world, the misfortunes, the wars, but also extraordinary things.

When you were in prison, how did painting help you?

When I was in prison, I was part of the phenomena that created the Prison Action Committee, and we changed prisons in the 70s, which hadn’t moved since, I’d say, the beginning of the 20th century. As a result, in addition to painting, which allowed me to feel good, we created a newspaper- well, it already existed, but we improved it enormously, it was in all the editorial offices, it was the political conscience of French prisoners. We organized movements, hunger strikes, rebellions too, to achieve a prison that was more liveable for everyone. I’ve always painted every day, and when I was in prison, I used as a cell as a studio, which was next to the cell used by the newspaper The Lock, I had visitors, guards who came in and out. I can paint anywhere.

Do you find artistic practice cathartic and do you think it’s a good conduit for emotions and a mode of therapy that can help incarcerated people, in particular?

As far as the figuration of emotions is concerned, of course. I’ve been thinking about this and I’ve put together a dossier for the Minister of Justice on this very subject, on the subject of art and prison.You have to realize that out of every 1,000 inmates, if you put a soccer ball in there, 800 will be playing soccer. If you put in paintbrushes, 5 or 6 will be interested. So, yes, it can be a good vehicle to elevate yourself and also have a different personality from the one that landed you in prison. I think it’s very interesting. It doesn’t work miracles unfortunately, but I think art does have a therapeutic effect.

Have you had people take up drawing, painting, discovering not necessarily a vocation, but perhaps a passion? And do people call you back today to thank you, for example, for having met you in prison?

As far as thanks are concerned, I’ve had many, many letters from parents, mothers and inmates too. But the inmates were very supportive.

When you work, what is your artistic process? Can you tell us a little about your painting process?

Well, first of all, I start with an idea, I feed this idea with documentation and then I synthesise it to get what I’m going to illustrate, what I’m going to use. When I draw, I first draw in charcoal to compose the picture, but I already see the finished picture, I know where I’m going to put the arm, the hand, the head, how I’m going to compose it, so I draw directly in charcoal. After that, I clean it up with pencil, because I use a lot of very bright colours, so I clean everything up well, erase everything and redo the very fine lines so that I have perfect definition and no graphic build-up in my colours, so that it stays really neat.

After that, I clean it up with pencil, because I use a lot of very bright colours, so I clean everything up well, erase everything and redo the very fine lines so that I have perfect definition and no graphic build-up in my colours, so that it stays really neat. I also think that the accidents in painting that have nourished art, I’d say, from the Impressionists to conceptual art, all these accidents have meant that with three colours, after a while, it’s important to have a craft, to know how to draw in order to be able to create something new. It’s no longer possible to draw like a child or a psychiatric patient at breakneck speed, because once you’ve done that, the result is something that no longer evolves.