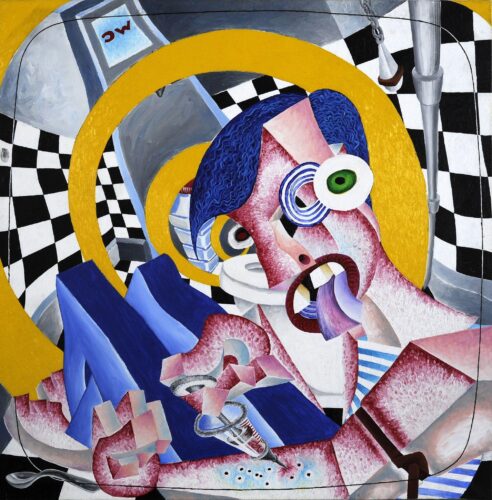

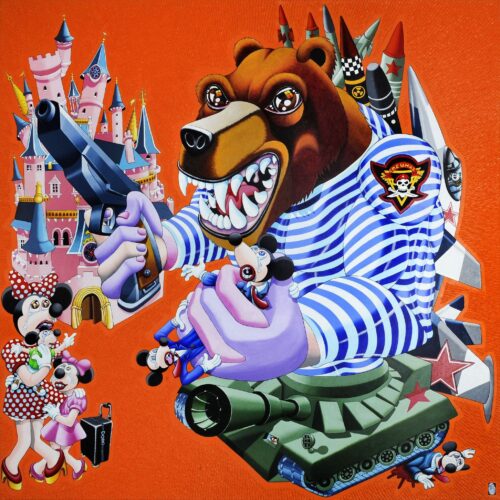

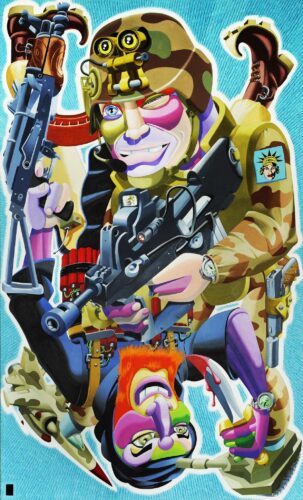

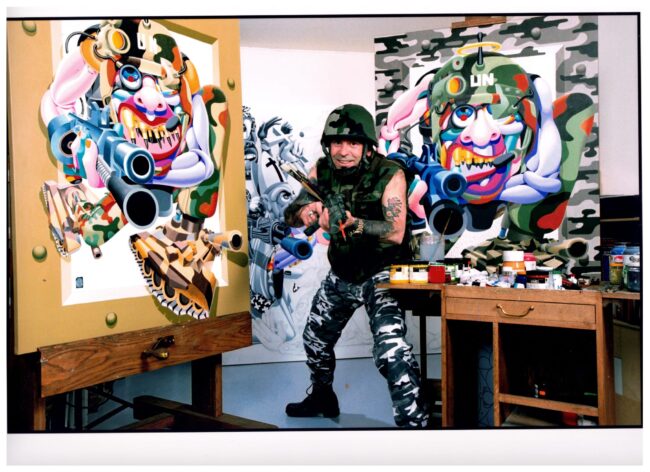

Opening on 7th June 2024 for 3 weeks at D’Stassi Art in London’s Shoreditch, the REBEL SOUL exhibition showcases 19 vivid figurative portraits and a custom Harley Davidson hand-painted by Chamizo who is regarded as one of the pioneers of street art. Inspired by lettrism, a unique alternative to graffiti and tag art, Chamizo is renowned for creating lettric abstraction-figuration, a style marked by raw, untamed expression and deep emotional truths.

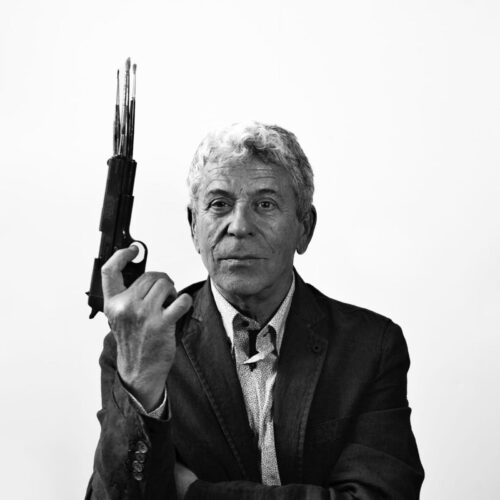

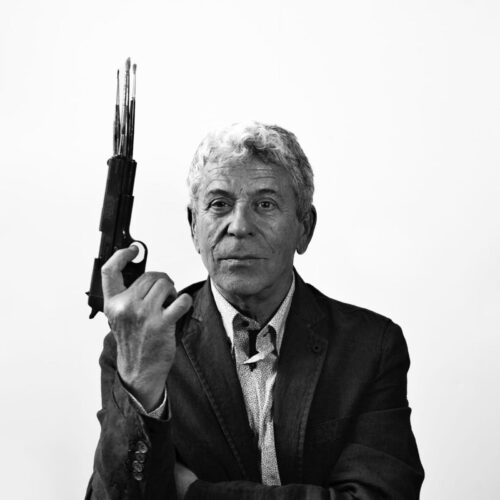

To be an artist with expression is one thing, but to be an artist with a story is another. Chamizo is an artist in the most authentic sense, his art informing his life and life informing his art. His life is a life lived to the fullest. However, Chamizo is more than a living example of the trope of a suffering artist: his art was born out of experiences that most people wouldn’t live through in a lifetime, but he channelled these experiences into visceral narratives that jump out of the canvas. As the saying goes, ‘You never know what you know until you do what you’ve never been told.’ This sentiment sets an artist on a path to iconism. Chamizo epitomizes the blend of art and lived experience. His work is an emblem of his turbulent journey, filled with political activism, personal tragedy, and relentless creativity.

Born into poverty in Cahors, France, on 15th October 1951, Chamizo’s early life was marked by stark contradictions and intense transformations. His is a tale of extraordinary, often near-death experiences that could rival a three-season Netflix docuseries or form the plot of a Martin Scorsese film. Full of intrigue, pain, suspense, joy, and triumph, Chamizo’s tale is as gripping as it is inspiring. Ultimately he channelled his angst, pain, activism, incarceration and protest into a completely unique artistic practice which germinated in prison, and led to recognition as an extraordinary and authentic artist whose work is collected and coveted by art world insiders including Alain Dominique Perrin of the Cartier Foundation, French singer-songwriter Hugues Aufray, French rapper and actor Didier Morville (better known by his stage name JoeyStarr), actress Marisa Berenson, French singer-songwriter Renaud, and Taittinger President Pierre-Emmanuel Taittinger.

Tom Stone sits down with Didier Chamizo to discuss his personal journey and inspirations.

TS: Didier, REBEL SOUL marks your first solo exhibition in the UK. How does this Milestone impact you personally and professionally, considering your extensive career?

DC: It’s wild that it took me so long to find my way to England? The vibe here is just electric, and I’m loving every minute of it. From the warm welcome from art lovers to the genuine hospitality from everyone I’ve met, it’s been a real treat.

And let me tell you about this bike show—I whipped up a custom bike because, well, I’m just nuts about motorcycles. It’s like adding a splash of excitement to my English adventure. Although I’ve had my art displayed at the Opéra Gallery in London, diving into something personal here feels like a whole new ballgame.

London has this rhythm, this pulse, that’s just infectious. I’ve been soaking it all in, meeting new folks, and feeling like I’ve finally found my groove here. England’s history as an ally during the war is one thing, but its cultural impact—think Rolling Stones, Beatles—has always resonated with me, even back in France. It’s like reconnecting with an old friend.

The warmth of the English people has made me feel like I’ve been here forever. And the connections I’ve made? They’re more than just professional—they’re like finding a second family, starting with Alex, who’s now my manager. Funny thing is, we crossed paths outside of London. Alex then hooks us up with the D’stassi gallery, where we hit it off with Mike and Eddy- total gems. All these people have this infectious energy, and they were so enthusiastic and excited about my work. It’s like we’ve formed this little work family, you know? Collaborative, dynamic, and just all-around lovely.

And get this—I’ve now been to London in Autumn, Winter, and Spring and haven’t experienced any rain…yet! Someone joked that I bring the sunshine with me whenever I visit. Talk about a warm welcome, right? It’s these little moments of camaraderie that make this whole experience even more special.

TS: Your participation in the May 1968 protests in France marked the beginning of your life of rebellion and defiance. How did these events influence your artistic journey and themes in your work?

DC: The atmosphere of rebellion and protest resonated deeply with me, stemming in part from my family background of deportees and resistance fighters who faced post-war poverty. I was born in ’51, and the ‘60s / 70s felt like a global awakening, albeit without the formal education to contextualise it. I truly believed that, like many people, we were heading towards a world where we would all be brothers and sisters. I hadn’t yet realised that there were many who didn’t want that. I guess it started with the music of the ’60s and ended with the hippie movement, sexual freedom, and all that. But that world didn’t come into being easily.

Initially, as I believed we were going to make a revolution, I burnt much of my early work in protest…1000 poems, hundreds of paintings and drawings… Rejecting the societal norms imposed on me from a young age—like being thrust into construction work at 13—I rebelled against a fate that stifled my artistic essence. After 3 years of working like that I thought well, either I die, or something else happens. And that was the revolution, so to speak. We did a bit of political agitation. We were certainly manipulated kids, like today. We believed in it, we were sincere. We were foolish, we were young. We engaged in political activism, albeit with the naïveté of youth.

Anyway, Yvon’s passing occurred around ’68, shortly after his 20th birthday, when I was around 19. He was my childhood companion, my closest ally. We used to mess around on mopeds. We messed around on motorcycles. We modified motorcycles. By “modifying,” I mean we prepared them for racing. We lived only with girls who loved motorcycles. We were always in the garage tinkering. And when we weren’t there, we were riding motorcycles like madmen. Actually, it was like Joe Bar Team before Joe Bar Team. Yes. And I wanted to add that, the loss of this very close friend was something very, very hard to live through. And perhaps in my search for perilous companionship, for adrenaline, as boys often do, I might have chosen the wrong friend at a bad time. There was a void. But in ’68, we truly believed we were going to do something wonderful. But in reality, we were the little puppets dancing. It’s almost the only period in my life when I didn’t paint. I was immersed in the ideals. I saw it as flamboyant heroism. I call it the temptation of the hero. But generally, it leads to foolishness.

Nevertheless, we participated in the fight for free abortion, for women’s freedom. We demonstrated for many, many things. And sometimes, more than just demonstrating. I won’t elaborate.

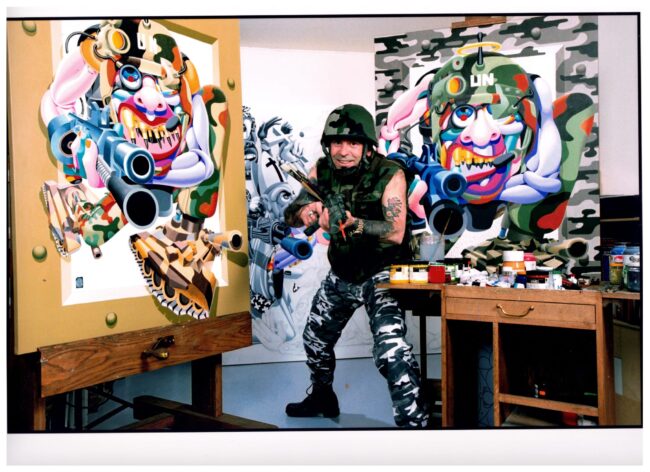

TS: Your art is influenced by lettrism and lettric abstraction-figuration. Can you explain how these styles shape your artistic vision and expression, particularly in the pieces featured in this exhibition?

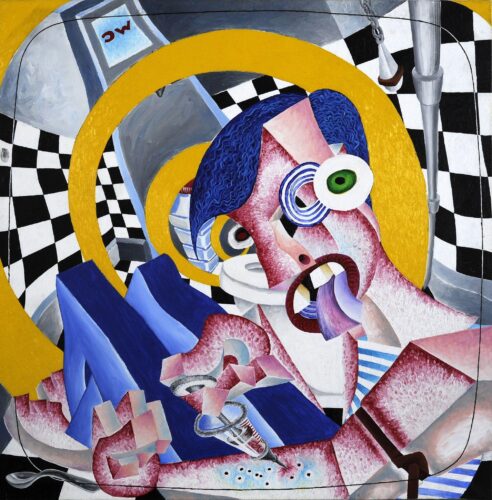

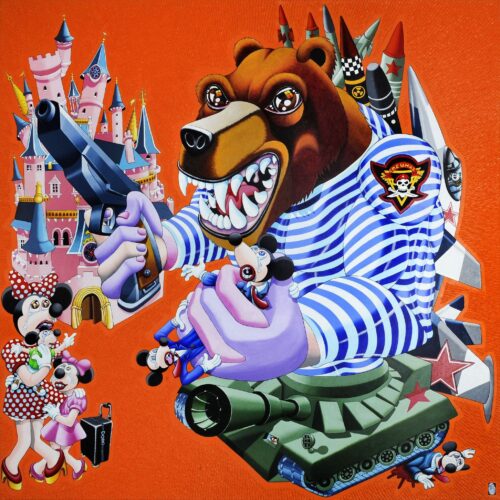

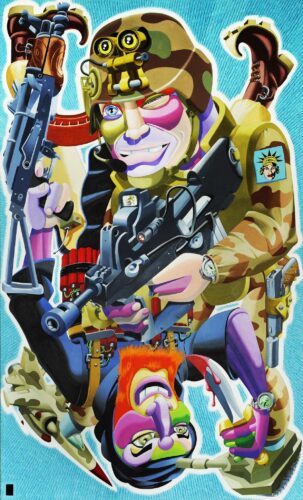

DC: I’ll talk about what I guess you could call theoretical painting. My work draws inspiration from Lettrism. Initially, I crafted characters, even in installations where I adorned walls and floors, blending abstraction with human rights—a kind of lettric abstraction. During my time in prison, I delved into various artistic realms within Lettrism, where the gestures resembled writing, eventually intertwining letters to the point of abstraction. As I created these abstractions, they surrounded my works, even sculptures, inviting people (prison guards and inmates at the time) to walk on them, physically, not virtually!, engaging with human rights-themed art. The guards were a bit shocked when they picked up on it. Took them a while as I wrote them in a dozen languages. I digress, through these abstractions, I discovered that certain letters could form pieces of characters. So I began crafting characters—flat, with or without reliefs, ranging from simplified to refined, sometimes employing capital letters. I experimented with letter formations, using, for instance, an F to depict shoulder, arm, and forearm muscles, along with the curve towards the elbow. This exploration led me to dress the characters and delve into the chromatic range of television, later incorporating colors from video games—an uncharted territory for traditional painting as far as I was concerned.

Despite the prevailing belief in the ’70s that painting had reached its demise, theorists who once championed conceptual art are now actively involved in painting or sculpture. Cartoons have always held my fascination, particularly due to their vibrant colors. Painting, which once mirrored reality, had to evolve beyond mere representation. Developing unique paths in painting allows for personal expression without viewers needing to identify the artist upon viewing the work.

Artificial intelligence intrigues me for its potential to offer new artistic possibilities. It can compress my body of work and suggest plastic solutions, although its effectiveness depends on the data it’s fed. As an assistant in artistic endeavors, AI could prove invaluable. However, its broader implications, especially in warfare and decision-making, raise concerns about its impact on humanity for me…I’ve now forgotten the question haha.

REBEL SOUL curated by D’Stassi and Henrik Alexander presents a compelling retrospective of my work, showcasing the evolution, particularly in Lettrism, from lettric abstraction to lettric figuration. This journey offers insight into the progression of my artistic exploration.

TS: You have experienced significant life events, including involvement in bank robberies, leading to multiple imprisonments. How did these tumultuous experiences influence the visceral narratives in your artwork?

DC: The tumultuous experiences of participating in bank robberies and facing multiple imprisonments have deeply influenced the visceral narratives in my work. These experiences made me value freedom in a profound way. I realised that while physical confinement was imposed upon me, my mind remained free, allowing me to continue my creative endeavours. In prison, I collaborated with friends to create a newspaper distributed across editorial offices, fostering connections with the outside world. Then we made a self-managed association.Through art, such as painting, I found a means to transcend the confines of my environment. Despite my past actions, I harbour no bitterness; instead, I am grateful for the opportunities society has afforded me. It has been decades since I engaged in criminal activities, and I have no desire to revisit that chapter of my life. In fact, I actively avoid movies depicting crime or incarceration, preferring to focus on more uplifting subjects.

TS: The custom Harley Davidson hand-painted by you is a unique centrepiece in this exhibition. What inspired you to integrate this element into your show, and what does it represent within the context of “REBEL SOUL“?

DC: Riding is also about moving freely in space, not being confined in a box. I’ve always been passionate about motorcycles; I’ve had a license to ride any engine size since I was 16. I’ve even competed, and still, from time to time, I hit up the race tracks. I f*cking love it. Maybe it’s dangerous, but it’s not more dangerous than crossing the street. Anyway, the decision to include a motorcycle in the exhibition stemmed from a collaboration with the incredibly passionate guys at Dirty Cats Motorcycles who I know through my manager Alex, co-owner of the business. They’re in London, they build bikes, they’re passionate and the fire was burning when I also met Filip, founder of Dirty Cats. They were on a super interesting project for the Bike Shed Moto Show, and it came about like that. Since I had already painted my Harley, other Harleys, and other expensive vehicles that were big hits, I thought it would be good. So, we went for it, doing something Punk Rock. I went for it with rear flames in the English flag, Punk Rock (it’s rock’n’roll), there’s Amy Winehouse, Johnny Rotten, the Clash, drugs, beer. Punk Rock… I’ve already put motorcycles in an exhibition, notably in Ibiza. I also made a motorcycle for the Womanity Foundation, which fetched an extraordinary price…anyway, I have fun, I love it. I have lots of helmets, shoes, and plenty of anything that falls on my lap that I’ve painted. A Ferrari for example, so why not another motorcycle? Plus, with the motorcycle, I have a passionate relationship. Motorcycles equate to freedom for me. I guess that’s not uncommon, but, hey!

TS: Meeting Alain Dominique Perrin of the Cartier Foundation was a turning point in your career. Can you share how this encounter influenced your path as an artist and your subsequent recognition in the art world?

DC: The meeting was quite extraordinary because it was my social worker, while I was in prison, who sent a dossier to her son who was a theater student. Later, he won seven Molières for an extraordinary play. Seven Molières are the top honors in French theater. The Oscars of theater. This young man saw Alain-Dominique Perrin because he was his temporary driver, parking in front of the Plaza. He handed him my dossier. A few days later, Alain-Dominique Perrin came to see me in prison. It was an encounter that greatly changed my life in the sense that I massively decreased the doubt I had about my work. I painted out of passion, I had always drawn and created original things, but I had never really been confronted with the advanced art world. I had done some things, some exhibitions, but that was it. I was a young artist. From then on, there was a friendship. While in prison, he’d bring me wine. The wine was prohibited in prison, but it was a nice gesture. And then, when I got out, he told me to come see him. He commissioned me with the Cartier Foundation. He bought some paintings from me. The Cartier Foundation and the Ministry of Culture commissioned a painted mural from me, Mur 2 Douelle. The theme was the history of wine. It’s a mural 120 meters long by 6 meters high. Everyone wanted the money for the mural, but no one wanted to paint it, so I did it. I tackled this mural, which is 120 meters long by 6 meters. Later, we celebrated

Alain-Dominique Perrin’s birthday. As an anecdote, he has a château on a hill with vineyards, and there was no place to make a cellar. So, he removed the hill, built a cellar, and put the hill and vineyards back. It’s an extraordinary thing.

I must say that I am someone very loyal to friendship. But here, I found a master. He is someone of great integrity and loyalty in friendship. Every time I asked him for something, or whenever he could support me, he did so with a lot of kindness, warmth, and humility. For his 50th birthday, I remember, of course, there was all the high society, I would say almost globally. Strange things happened. For example, I remember we were biking with César and Alain-Dominique. I said, “it’s funny, she looks a lot like Tina Turner”. He looked at me and said, but that is Tina Turner. I laughed. Imagine being fresh out of prison. That same evening, everyone was there with gifts and all kinds of things. I brought a tube of shoe polish and a brush. I told him “here, you’ll need this because you’ll get your shoes shined all evening”.

TS: Despite your international acclaim, you have remained reclusive, often shunning the public spotlight. How do you feel about the art world’s commercialism, and what drives your decision to maintain such a private persona?

DC: I would say that when I was younger, it was very hard to part with my works, somewhat like parting with one’s children. That’s something difficult at the beginning, but later, to continue painting, you need money. Well, you need money, and then there are the art dealers, the merchants, or the gallerists; they prepare an exhibition, they invest time, so if they make money, you make money too. But it’s inevitable. However, there is an authenticity that I am keen to preserve, meaning I create all my art, I draw them, I paint them, I sculpt them, I don’t produce prints where a machine prints my paintings. I want the person who buys a painting to have a real painting.

I don’t know how consciously reclusive I am, but painting, one must admit, is, we could call it a time-consuming mistress, to use a trendy term [in french]. When you’ve spent twelve hours in the studio, you don’t really feel like gesticulating under the spotlights, actually. So, it’s a matter of time management. However, I recognize that when I do an exhibition, meet people, and feed off their energy, it does me a lot of good. I mean, it’s the only moment when you receive some applause for the work you’ve done. Otherwise, the canvases are there, and once they’re finished, the most important one is the one I’m currently working on. But it’s true that you can’t do without the art market. Moreover, it would be very tedious for me to discuss this and that for hours. And then, organizing an exhibition, managing relationships, I couldn’t do it alone. But otherwise, success doesn’t bother me. But I have to preserve this time in the studio. Otherwise, I wouldn’t produce much and I wouldn’t be sane. Strangely I have a similar routine as the one I had in prison. We all do what we can to remain sane. And for me, that is not the spotlight. In the past, that has done me more harm than good…

TS: What gives you the most pleasure?

DC: When you work and see the painting progress, and it’s how you want it, well constructed, it’s satisfying. But since others look at it, it’s a story for three. There must be a work, an artist, and a viewer. Without the viewer, there is no artist, no work. And also, one must know that painting, like all artistic endeavors, it’s also a gesture of love towards people. It’s like saying, “Look at what I’m doing for you, I’m giving you my soul, you give me love back, it’s cool.” Haha

TS: Your journey from a welder apprentice to a renowned artist, with your political activism and personal challenges, has been extraordinary. How do you perceive your legacy, and what message do you hope your art conveys to future generations?

DC: At the age of 13, I was already struggling greatly with the death of my 2-year-old sister, who had died in front of me when I was 11. My parents took me out of school to put me in construction. So, I became an apprentice welder. You should know that at the time, in 1964, we easily worked 10 hours a day and on Saturday mornings, I found myself with my hands in the metal, in the cold, carrying things, melting things together. But I already had my artistic nature, which was very frustrated. I saw it, I suffered greatly. I lasted 3 years. I lasted 3 years… And at some point, I said to myself, it’s impossible for me to accept this. So, it’s true that after, I left more or less with ’68. Then, I did some foolish things that I won’t mention. But there’s no point in whining about it since it can’t be changed. But I wanted something else. In fact, I wanted to exist. I wanted to be who I am today. But I didn’t know how to define it. I was a kid from a disadvantaged family. And so, I’ve always had a lot of energy. Both to fight for my freedom and for painting. With a great willingness to work. And I know that when I have a goal, I go all out. I don’t do a little of this, a little of that. When I do something, I go all out. The day I said, for example, painting is it. I had a very serious motorcycle accident. I spent 2 years in a wheelchair in the hospital. I said, painting, that’s what I love, that’s what I do, and I’ll do it all the way.

I was awakened, actually, quite brutally. Because I was 30 years old. I was a pretty charming dude. I had a lot of success. And at 30, you feel immortal. Which is not entirely abnormal. And then, a drunk guy hit me with his car on the highway. I ended up in a coma for a month, a year in the hospital, 2 years in a wheelchair, 17 operations. That also changes your life. Because it teaches you humility. It teaches you to need someone, in my case, even to get up or to pee. Which is not very pleasant. So there’s that. But above all, I almost died. Really died, disappeared from the face of the Earth. And from there, I said to myself, what do you love the most?

You mustn’t waste time, you need to pursue what you love. And there, I would say that the caterpillar was unfolding its wings to become a butterfly. Something like that.

When people look at my paintings, it’s the gaze of an artist during his era. And sometimes I try to… Well, for example, we see war on television. But we see so much of it in movies that we don’t really see the dead anymore. Staged in a painting, the image is more striking and can lead to thinking, I hope, that war is not a good thing. For example, I protested for this and that… I prefer that we all protest against war. It’s more intelligent. But I leave messages like that, about my vision of the world and what I hope for. Of course, I hope that one day on Earth, we will regulate the population, stop these stupid wars, and no longer need borders, because we are on an extraordinary extraterrestrial vehicle. Because we are on an extraordinary spaceship in an absolutely incredible universe. Everything is magnificent: animals, nature, plants. And even we, humans, are sometimes really magnificent too. But sometimes we aren’t always. And if painting… I know you can’t stop a war with a painting. But if it can lead to thinking, just a little, that war isn’t always good, that would be a good thing. In any case, long live freedom and long live love.

TS: What do you want to be remembered for?

DC: That I was a great motorcyclist, haha. No, that I was someone really authentic. And my work is authentic because I put my energy into it, I put everything, I put my love into it. If I had a piece of advice for young people, since they are the future, I would tell them, if you have the opportunity to do what you love, choose the happiness of doing what you love rather than chasing dreams for more money and not living. Live, and especially try to thrive in what you love. In real life, you can thrive in a job you love. And it is a great privilege to do what you love. If you have this opportunity, you should take it. But be careful, the road is not the easiest. It’s the steep path through bushes and thorns. But it is a great strength to be free and a great strength to do what you love. It’s a great privilege. My qualities, I think, are authenticity but also combativeness. I can say that I don’t let much get me down and that I always react with a lot of courage to achieve what I want to achieve.

TS: What can stop you?

DC: What can stop me? I don’t know, an atomic bomb?

D’Stassi Art

12-18 Hoxton Street (Entrance on Drysdale St) London N1 6NG

https://dstassiart.com/blogs/exhibitions/didier-chamizo-uk-debut-rebel-soul

Opening on 7th June 2024 for 3 weeks at D’Stassi Art in London’s Shoreditch, the REBEL SOUL exhibition showcases 19 vivid figurative portraits and a custom Harley Davidson hand-painted by Chamizo who is regarded as one of the pioneers of street art. Inspired by lettrism, a unique alternative to graffiti and tag art, Chamizo is renowned for creating lettric abstraction-figuration, a style marked by raw, untamed expression and deep emotional truths.

To be an artist with expression is one thing, but to be an artist with a story is another. Chamizo is an artist in the most authentic sense, his art informing his life and life informing his art. His life is a life lived to the fullest. However, Chamizo is more than a living example of the trope of a suffering artist: his art was born out of experiences that most people wouldn’t live through in a lifetime, but he channelled these experiences into visceral narratives that jump out of the canvas. As the saying goes, ‘You never know what you know until you do what you’ve never been told.’ This sentiment sets an artist on a path to iconism. Chamizo epitomizes the blend of art and lived experience. His work is an emblem of his turbulent journey, filled with political activism, personal tragedy, and relentless creativity.

Born into poverty in Cahors, France, on 15th October 1951, Chamizo’s early life was marked by stark contradictions and intense transformations. His is a tale of extraordinary, often near-death experiences that could rival a three-season Netflix docuseries or form the plot of a Martin Scorsese film. Full of intrigue, pain, suspense, joy, and triumph, Chamizo’s tale is as gripping as it is inspiring. Ultimately he channelled his angst, pain, activism, incarceration and protest into a completely unique artistic practice which germinated in prison, and led to recognition as an extraordinary and authentic artist whose work is collected and coveted by art world insiders including Alain Dominique Perrin of the Cartier Foundation, French singer-songwriter Hugues Aufray, French rapper and actor Didier Morville (better known by his stage name JoeyStarr), actress Marisa Berenson, French singer-songwriter Renaud, and Taittinger President Pierre-Emmanuel Taittinger.

Tom Stone sits down with Didier Chamizo to discuss his personal journey and inspirations.

TS: Didier, REBEL SOUL marks your first solo exhibition in the UK. How does this Milestone impact you personally and professionally, considering your extensive career?

DC: It’s wild that it took me so long to find my way to England? The vibe here is just electric, and I’m loving every minute of it. From the warm welcome from art lovers to the genuine hospitality from everyone I’ve met, it’s been a real treat.

And let me tell you about this bike show—I whipped up a custom bike because, well, I’m just nuts about motorcycles. It’s like adding a splash of excitement to my English adventure. Although I’ve had my art displayed at the Opéra Gallery in London, diving into something personal here feels like a whole new ballgame.

London has this rhythm, this pulse, that’s just infectious. I’ve been soaking it all in, meeting new folks, and feeling like I’ve finally found my groove here. England’s history as an ally during the war is one thing, but its cultural impact—think Rolling Stones, Beatles—has always resonated with me, even back in France. It’s like reconnecting with an old friend.

The warmth of the English people has made me feel like I’ve been here forever. And the connections I’ve made? They’re more than just professional—they’re like finding a second family, starting with Alex, who’s now my manager. Funny thing is, we crossed paths outside of London. Alex then hooks us up with the D’stassi gallery, where we hit it off with Mike and Eddy- total gems. All these people have this infectious energy, and they were so enthusiastic and excited about my work. It’s like we’ve formed this little work family, you know? Collaborative, dynamic, and just all-around lovely.

And get this—I’ve now been to London in Autumn, Winter, and Spring and haven’t experienced any rain…yet! Someone joked that I bring the sunshine with me whenever I visit. Talk about a warm welcome, right? It’s these little moments of camaraderie that make this whole experience even more special.

TS: Your participation in the May 1968 protests in France marked the beginning of your life of rebellion and defiance. How did these events influence your artistic journey and themes in your work?

DC: The atmosphere of rebellion and protest resonated deeply with me, stemming in part from my family background of deportees and resistance fighters who faced post-war poverty. I was born in ’51, and the ‘60s / 70s felt like a global awakening, albeit without the formal education to contextualise it. I truly believed that, like many people, we were heading towards a world where we would all be brothers and sisters. I hadn’t yet realised that there were many who didn’t want that. I guess it started with the music of the ’60s and ended with the hippie movement, sexual freedom, and all that. But that world didn’t come into being easily.

Initially, as I believed we were going to make a revolution, I burnt much of my early work in protest…1000 poems, hundreds of paintings and drawings… Rejecting the societal norms imposed on me from a young age—like being thrust into construction work at 13—I rebelled against a fate that stifled my artistic essence. After 3 years of working like that I thought well, either I die, or something else happens. And that was the revolution, so to speak. We did a bit of political agitation. We were certainly manipulated kids, like today. We believed in it, we were sincere. We were foolish, we were young. We engaged in political activism, albeit with the naïveté of youth.

Anyway, Yvon’s passing occurred around ’68, shortly after his 20th birthday, when I was around 19. He was my childhood companion, my closest ally. We used to mess around on mopeds. We messed around on motorcycles. We modified motorcycles. By “modifying,” I mean we prepared them for racing. We lived only with girls who loved motorcycles. We were always in the garage tinkering. And when we weren’t there, we were riding motorcycles like madmen. Actually, it was like Joe Bar Team before Joe Bar Team. Yes. And I wanted to add that, the loss of this very close friend was something very, very hard to live through. And perhaps in my search for perilous companionship, for adrenaline, as boys often do, I might have chosen the wrong friend at a bad time. There was a void. But in ’68, we truly believed we were going to do something wonderful. But in reality, we were the little puppets dancing. It’s almost the only period in my life when I didn’t paint. I was immersed in the ideals. I saw it as flamboyant heroism. I call it the temptation of the hero. But generally, it leads to foolishness.

Nevertheless, we participated in the fight for free abortion, for women’s freedom. We demonstrated for many, many things. And sometimes, more than just demonstrating. I won’t elaborate.

TS: Your art is influenced by lettrism and lettric abstraction-figuration. Can you explain how these styles shape your artistic vision and expression, particularly in the pieces featured in this exhibition?

DC: I’ll talk about what I guess you could call theoretical painting. My work draws inspiration from Lettrism. Initially, I crafted characters, even in installations where I adorned walls and floors, blending abstraction with human rights—a kind of lettric abstraction. During my time in prison, I delved into various artistic realms within Lettrism, where the gestures resembled writing, eventually intertwining letters to the point of abstraction. As I created these abstractions, they surrounded my works, even sculptures, inviting people (prison guards and inmates at the time) to walk on them, physically, not virtually!, engaging with human rights-themed art. The guards were a bit shocked when they picked up on it. Took them a while as I wrote them in a dozen languages. I digress, through these abstractions, I discovered that certain letters could form pieces of characters. So I began crafting characters—flat, with or without reliefs, ranging from simplified to refined, sometimes employing capital letters. I experimented with letter formations, using, for instance, an F to depict shoulder, arm, and forearm muscles, along with the curve towards the elbow. This exploration led me to dress the characters and delve into the chromatic range of television, later incorporating colors from video games—an uncharted territory for traditional painting as far as I was concerned.

Despite the prevailing belief in the ’70s that painting had reached its demise, theorists who once championed conceptual art are now actively involved in painting or sculpture. Cartoons have always held my fascination, particularly due to their vibrant colors. Painting, which once mirrored reality, had to evolve beyond mere representation. Developing unique paths in painting allows for personal expression without viewers needing to identify the artist upon viewing the work.

Artificial intelligence intrigues me for its potential to offer new artistic possibilities. It can compress my body of work and suggest plastic solutions, although its effectiveness depends on the data it’s fed. As an assistant in artistic endeavors, AI could prove invaluable. However, its broader implications, especially in warfare and decision-making, raise concerns about its impact on humanity for me…I’ve now forgotten the question haha.

REBEL SOUL curated by D’Stassi and Henrik Alexander presents a compelling retrospective of my work, showcasing the evolution, particularly in Lettrism, from lettric abstraction to lettric figuration. This journey offers insight into the progression of my artistic exploration.

TS: You have experienced significant life events, including involvement in bank robberies, leading to multiple imprisonments. How did these tumultuous experiences influence the visceral narratives in your artwork?

DC: The tumultuous experiences of participating in bank robberies and facing multiple imprisonments have deeply influenced the visceral narratives in my work. These experiences made me value freedom in a profound way. I realised that while physical confinement was imposed upon me, my mind remained free, allowing me to continue my creative endeavours. In prison, I collaborated with friends to create a newspaper distributed across editorial offices, fostering connections with the outside world. Then we made a self-managed association.Through art, such as painting, I found a means to transcend the confines of my environment. Despite my past actions, I harbour no bitterness; instead, I am grateful for the opportunities society has afforded me. It has been decades since I engaged in criminal activities, and I have no desire to revisit that chapter of my life. In fact, I actively avoid movies depicting crime or incarceration, preferring to focus on more uplifting subjects.

TS: The custom Harley Davidson hand-painted by you is a unique centrepiece in this exhibition. What inspired you to integrate this element into your show, and what does it represent within the context of “REBEL SOUL“?

DC: Riding is also about moving freely in space, not being confined in a box. I’ve always been passionate about motorcycles; I’ve had a license to ride any engine size since I was 16. I’ve even competed, and still, from time to time, I hit up the race tracks. I f*cking love it. Maybe it’s dangerous, but it’s not more dangerous than crossing the street. Anyway, the decision to include a motorcycle in the exhibition stemmed from a collaboration with the incredibly passionate guys at Dirty Cats Motorcycles who I know through my manager Alex, co-owner of the business. They’re in London, they build bikes, they’re passionate and the fire was burning when I also met Filip, founder of Dirty Cats. They were on a super interesting project for the Bike Shed Moto Show, and it came about like that. Since I had already painted my Harley, other Harleys, and other expensive vehicles that were big hits, I thought it would be good. So, we went for it, doing something Punk Rock. I went for it with rear flames in the English flag, Punk Rock (it’s rock’n’roll), there’s Amy Winehouse, Johnny Rotten, the Clash, drugs, beer. Punk Rock… I’ve already put motorcycles in an exhibition, notably in Ibiza. I also made a motorcycle for the Womanity Foundation, which fetched an extraordinary price…anyway, I have fun, I love it. I have lots of helmets, shoes, and plenty of anything that falls on my lap that I’ve painted. A Ferrari for example, so why not another motorcycle? Plus, with the motorcycle, I have a passionate relationship. Motorcycles equate to freedom for me. I guess that’s not uncommon, but, hey!

TS: Meeting Alain Dominique Perrin of the Cartier Foundation was a turning point in your career. Can you share how this encounter influenced your path as an artist and your subsequent recognition in the art world?

DC: The meeting was quite extraordinary because it was my social worker, while I was in prison, who sent a dossier to her son who was a theater student. Later, he won seven Molières for an extraordinary play. Seven Molières are the top honors in French theater. The Oscars of theater. This young man saw Alain-Dominique Perrin because he was his temporary driver, parking in front of the Plaza. He handed him my dossier. A few days later, Alain-Dominique Perrin came to see me in prison. It was an encounter that greatly changed my life in the sense that I massively decreased the doubt I had about my work. I painted out of passion, I had always drawn and created original things, but I had never really been confronted with the advanced art world. I had done some things, some exhibitions, but that was it. I was a young artist. From then on, there was a friendship. While in prison, he’d bring me wine. The wine was prohibited in prison, but it was a nice gesture. And then, when I got out, he told me to come see him. He commissioned me with the Cartier Foundation. He bought some paintings from me. The Cartier Foundation and the Ministry of Culture commissioned a painted mural from me, Mur 2 Douelle. The theme was the history of wine. It’s a mural 120 meters long by 6 meters high. Everyone wanted the money for the mural, but no one wanted to paint it, so I did it. I tackled this mural, which is 120 meters long by 6 meters. Later, we celebrated

Alain-Dominique Perrin’s birthday. As an anecdote, he has a château on a hill with vineyards, and there was no place to make a cellar. So, he removed the hill, built a cellar, and put the hill and vineyards back. It’s an extraordinary thing.

I must say that I am someone very loyal to friendship. But here, I found a master. He is someone of great integrity and loyalty in friendship. Every time I asked him for something, or whenever he could support me, he did so with a lot of kindness, warmth, and humility. For his 50th birthday, I remember, of course, there was all the high society, I would say almost globally. Strange things happened. For example, I remember we were biking with César and Alain-Dominique. I said, “it’s funny, she looks a lot like Tina Turner”. He looked at me and said, but that is Tina Turner. I laughed. Imagine being fresh out of prison. That same evening, everyone was there with gifts and all kinds of things. I brought a tube of shoe polish and a brush. I told him “here, you’ll need this because you’ll get your shoes shined all evening”.

TS: Despite your international acclaim, you have remained reclusive, often shunning the public spotlight. How do you feel about the art world’s commercialism, and what drives your decision to maintain such a private persona?

DC: I would say that when I was younger, it was very hard to part with my works, somewhat like parting with one’s children. That’s something difficult at the beginning, but later, to continue painting, you need money. Well, you need money, and then there are the art dealers, the merchants, or the gallerists; they prepare an exhibition, they invest time, so if they make money, you make money too. But it’s inevitable. However, there is an authenticity that I am keen to preserve, meaning I create all my art, I draw them, I paint them, I sculpt them, I don’t produce prints where a machine prints my paintings. I want the person who buys a painting to have a real painting.

I don’t know how consciously reclusive I am, but painting, one must admit, is, we could call it a time-consuming mistress, to use a trendy term [in french]. When you’ve spent twelve hours in the studio, you don’t really feel like gesticulating under the spotlights, actually. So, it’s a matter of time management. However, I recognize that when I do an exhibition, meet people, and feed off their energy, it does me a lot of good. I mean, it’s the only moment when you receive some applause for the work you’ve done. Otherwise, the canvases are there, and once they’re finished, the most important one is the one I’m currently working on. But it’s true that you can’t do without the art market. Moreover, it would be very tedious for me to discuss this and that for hours. And then, organizing an exhibition, managing relationships, I couldn’t do it alone. But otherwise, success doesn’t bother me. But I have to preserve this time in the studio. Otherwise, I wouldn’t produce much and I wouldn’t be sane. Strangely I have a similar routine as the one I had in prison. We all do what we can to remain sane. And for me, that is not the spotlight. In the past, that has done me more harm than good…

TS: What gives you the most pleasure?

DC: When you work and see the painting progress, and it’s how you want it, well constructed, it’s satisfying. But since others look at it, it’s a story for three. There must be a work, an artist, and a viewer. Without the viewer, there is no artist, no work. And also, one must know that painting, like all artistic endeavors, it’s also a gesture of love towards people. It’s like saying, “Look at what I’m doing for you, I’m giving you my soul, you give me love back, it’s cool.” Haha

TS: Your journey from a welder apprentice to a renowned artist, with your political activism and personal challenges, has been extraordinary. How do you perceive your legacy, and what message do you hope your art conveys to future generations?

DC: At the age of 13, I was already struggling greatly with the death of my 2-year-old sister, who had died in front of me when I was 11. My parents took me out of school to put me in construction. So, I became an apprentice welder. You should know that at the time, in 1964, we easily worked 10 hours a day and on Saturday mornings, I found myself with my hands in the metal, in the cold, carrying things, melting things together. But I already had my artistic nature, which was very frustrated. I saw it, I suffered greatly. I lasted 3 years. I lasted 3 years… And at some point, I said to myself, it’s impossible for me to accept this. So, it’s true that after, I left more or less with ’68. Then, I did some foolish things that I won’t mention. But there’s no point in whining about it since it can’t be changed. But I wanted something else. In fact, I wanted to exist. I wanted to be who I am today. But I didn’t know how to define it. I was a kid from a disadvantaged family. And so, I’ve always had a lot of energy. Both to fight for my freedom and for painting. With a great willingness to work. And I know that when I have a goal, I go all out. I don’t do a little of this, a little of that. When I do something, I go all out. The day I said, for example, painting is it. I had a very serious motorcycle accident. I spent 2 years in a wheelchair in the hospital. I said, painting, that’s what I love, that’s what I do, and I’ll do it all the way.

I was awakened, actually, quite brutally. Because I was 30 years old. I was a pretty charming dude. I had a lot of success. And at 30, you feel immortal. Which is not entirely abnormal. And then, a drunk guy hit me with his car on the highway. I ended up in a coma for a month, a year in the hospital, 2 years in a wheelchair, 17 operations. That also changes your life. Because it teaches you humility. It teaches you to need someone, in my case, even to get up or to pee. Which is not very pleasant. So there’s that. But above all, I almost died. Really died, disappeared from the face of the Earth. And from there, I said to myself, what do you love the most?

You mustn’t waste time, you need to pursue what you love. And there, I would say that the caterpillar was unfolding its wings to become a butterfly. Something like that.

When people look at my paintings, it’s the gaze of an artist during his era. And sometimes I try to… Well, for example, we see war on television. But we see so much of it in movies that we don’t really see the dead anymore. Staged in a painting, the image is more striking and can lead to thinking, I hope, that war is not a good thing. For example, I protested for this and that… I prefer that we all protest against war. It’s more intelligent. But I leave messages like that, about my vision of the world and what I hope for. Of course, I hope that one day on Earth, we will regulate the population, stop these stupid wars, and no longer need borders, because we are on an extraordinary extraterrestrial vehicle. Because we are on an extraordinary spaceship in an absolutely incredible universe. Everything is magnificent: animals, nature, plants. And even we, humans, are sometimes really magnificent too. But sometimes we aren’t always. And if painting… I know you can’t stop a war with a painting. But if it can lead to thinking, just a little, that war isn’t always good, that would be a good thing. In any case, long live freedom and long live love.

TS: What do you want to be remembered for?

DC: That I was a great motorcyclist, haha. No, that I was someone really authentic. And my work is authentic because I put my energy into it, I put everything, I put my love into it. If I had a piece of advice for young people, since they are the future, I would tell them, if you have the opportunity to do what you love, choose the happiness of doing what you love rather than chasing dreams for more money and not living. Live, and especially try to thrive in what you love. In real life, you can thrive in a job you love. And it is a great privilege to do what you love. If you have this opportunity, you should take it. But be careful, the road is not the easiest. It’s the steep path through bushes and thorns. But it is a great strength to be free and a great strength to do what you love. It’s a great privilege. My qualities, I think, are authenticity but also combativeness. I can say that I don’t let much get me down and that I always react with a lot of courage to achieve what I want to achieve.

TS: What can stop you?

DC: What can stop me? I don’t know, an atomic bomb?

D’Stassi Art

12-18 Hoxton Street (Entrance on Drysdale St) London N1 6NG

https://dstassiart.com/blogs/exhibitions/didier-chamizo-uk-debut-rebel-soul